In just over four weeks I will hear a live rendition of an art song I have been working on with a young composer as part of Art Song Lab 2015. To say I’m excited is somewhat of an understatement. I’m not a writer who does readings. I have yet to make my voice heard on the Vancouver writers’ scene, and so this opportunity to take part in ASL 2015 is a significant step for me in terms of visibility and professional development. It is a chance for words I have written to be read (or, rather, sung) on stage in front of a live audience. I’m simultaneously thrilled and terrified.

In just over four weeks I will hear a live rendition of an art song I have been working on with a young composer as part of Art Song Lab 2015. To say I’m excited is somewhat of an understatement. I’m not a writer who does readings. I have yet to make my voice heard on the Vancouver writers’ scene, and so this opportunity to take part in ASL 2015 is a significant step for me in terms of visibility and professional development. It is a chance for words I have written to be read (or, rather, sung) on stage in front of a live audience. I’m simultaneously thrilled and terrified.

As a freelance writer working for the most part in a vacuum, with only my trusty border collie to provide feedback, the idea of collaborating with a composer to create an entirely new art song from scratch was at once exciting and challenging. I am used to being in full control of the creative process. I write, I edit, I publish; involving beta-readers and proofreaders as necessary, designers for book covers and such, but with the final say on all my projects. This time, I would have to relinquish control.

Any flutters of initial reluctance quickly evaporated as I waited to hear who I’d be paired with for the project. I was eager to get started, to throw around ideas and to open the door to criticism of my work before I let it out into the world.

So, when I was e-introduced to my composer, Jared Hedges, I did the requisite GStalk to check out his credentials, past work, and general online presence, imagining that as young(ish!) artists we would have some common ground on which to stand while we figured out what our art song would be about. I admit, I was a bit taken aback by the discovery that Jared attends an evangelical Christian college in the US.

I’m an atheist, queer, poly, feminist with liberal, if not radical, political leanings. This could be fun, I thought, and then an amused friend discovered the college’s covenant, which lists homosexuality alongside thievery, evil desires, and other character traits to be avoided. It also stresses that sex (however that looks) be limited to heterosexual, monogamous marriage. And, perhaps most importantly, it stresses that students at the college consider these ideals when engaging with and creating media. So much for the unicorns and rainbows and explicitly homoerotic motifs I had planned for our art song. (I’m kidding, I promise.)

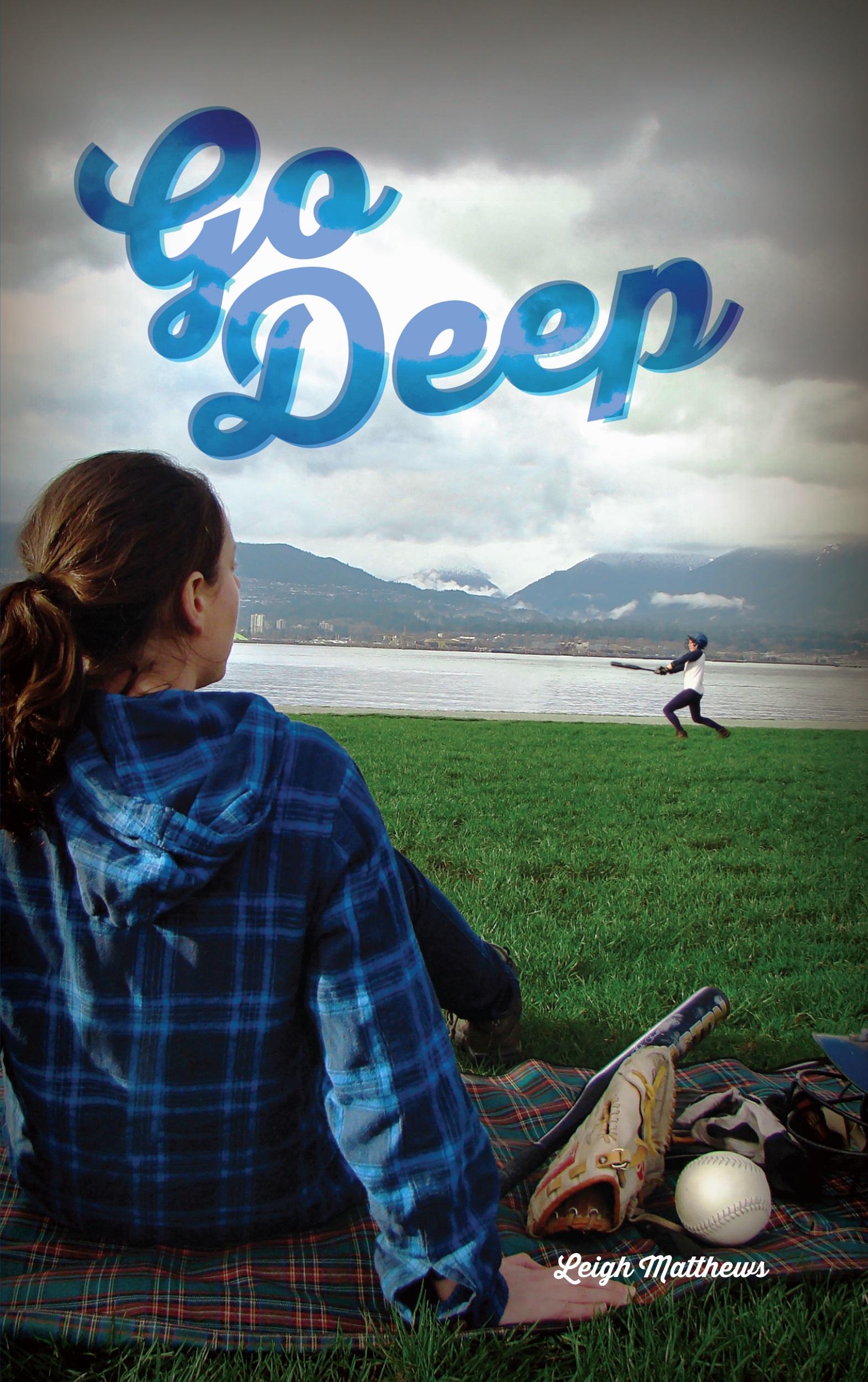

The discovery of this covenant certainly raised an interesting question for me about how my queer identify might influence my creative projects. It’s been a while since I felt constrained in my writing, and that constraint was largely self-inflicted, based on the fear of quick judgement about my character and lifestyle. Given that my latest novel is a modern take on lesbian pulp fiction, it should be pretty obvious that I’ve mellowed with age and am less concerned with being pigeonholed and judged than I am with ensuring the representation of the incredible diversity of the LGBTQUIA2S community.

The idea of someone placing restrictions on my freedom of speech was rather unattractive. The literary closet is pretty stuffy, and I’ve become quite acclimated to the fresh air of Vancouver.

Realising I was heading toward panic with no real knowledge of my creative partner’s views, I got in touch to check some things: firstly, that he knew a little about me and my work; secondly, that he still wanted to work with me; and, thirdly, that he wouldn’t get kicked out of school for doing so. His answer? A resounding yes to working with me, but with the caveat that he’d rather our art song not contain queer themes.

Hm.

Where does that leave a queer writer? How fundamental is one’s queerness to the creative process? This dilemma set up an interesting challenge, asking me to really look at how my queerness influences my art, to see if it really is a keystone for all that I produce. Stripped of queerness, what is left in my work?

Turned on its head, the proposition is akin to asking a straight person to write a poem with no straight themes: No heteronormative love poem; No gender binary; No reflection of a fundamental part of their identity, however unquestioned; No adherence to normative narratives. Looked at that way, this describes most of my current work, in that I strive to present a more nuanced view of life, be that queering sexuality, gender, relationship models, or systems of oppression affecting people of colour, women, trans people, and animals.

In essence, I believe that my queerness extends beyond sexuality to encompass a wider view of the world, and to acknowledge the grey areas of life, the nuances. I believe that accepting my queerness and engaging with it may actually make me a better poet.

Given that I’ve always been out to myself and a handful of people close to me, but only fairly recently out to everyone in my life, I reflected on how my writing has changed from when I was living in the UK (not really out), to living in Vancouver (very much out and part of the queer community). I’m still (usually!) pretty private and only vaguely autobiographical in my writing, but that distance is an aesthetic choice now, not a necessity for invisibility and survival. To make myself invisible seemed like a big step backward.

So how to overcome this peculiar constraint?

The writers and artists among you will probably already know what happened next: I wrote about it; exploring the very concept of constraint, of ideological difference, of entanglement and discordance. In essence, the queer artist in me revealed herself and told me that she wouldn’t be quieted, not again.

I wrote about the need we have, as humans, to categorise oddity as undesirable, to make things neat and tidy, to reshape the incongruent into a recognisable, simple form. I examined the idea of pathologising disharmony, of making discordant rhythms harmonious. I used the heart as a symbol, its normal rhythms, its abnormal rhythms, and our ability to alter that rhythm artificially. I wrote about how this quashing of strangeness, this silencing or shouting down, allows the dominant to pretend that the other is gone. But a person who is quiet, silent even, is still a person. Their voice is still their voice, their difference still difference. An imposed heartbeat, however normal, is still an imposition.

I thought about Beethoven, and how some music scholars believe his arrhythmic heart inspired his compositions. I recognised that these references would not be laid out in the poem, but that they were distilled instead, and were essential to the process of writing this piece.

In thinking about these things, I got excited by the idea of entanglement, of involving the audience in the discordance, causing discomfort so as to prompt a desire for normality and regulation. I wanted our art song not only to represent our collaboration, but to draw in the audience as collaborators. I wanted to have those listening to go through the same process of recognising disharmony, willing it to be normalised, and then experiencing the sadness when otherness is silenced. I wanted them to appreciate the loss of richness when nuance is ground down by normativity.

The piece I wrote was an attempt to speak of difference and sameness, the things lying underneath what we say and how we behave. On the surface it looked like an unfinished conversation between lovers, broken by death or simple misunderstanding. It was all the important unspoken things and all the things spoken that would have been better left unsaid. It was also a request for a confidante, for someone to listen and hear the truth of the protagonist, not to smother their words with the timeworn narrative of lost love.

I wanted it to speak of the similarities of rhythms shared by all humans, and of the problems we face if we assume that someone’s surface accurately represents what’s below. I wanted to sound out the temptation we often feel to subsume discordant sounds into a more comfortable, familiar rhythm.

I got to thinking about Kant, about schematics, and about the difficulty of changing the way we have learnt to view

the world, and of the things we miss if our schema is too rigid. The poem is one of heartbreak, not only at the end of the protagonist’s relationship, but also for the inability for the chosen confidante to truly hear about that pain.

In a wider sense, I was thinking of the failure of well-intentioned charity, and how not truly listening to a person, or to a group of people, denies them their personhood, their autonomy, disregarding their history and knowledge as we go about trying to fix that which we perceive as broken. I thought about aid agencies imposing value systems and then wondering why interventions fail.

The poem was about more than a break-up, a lost love. It was, instead, an appeal to respect connection, entanglement, shared humanity and compassion.

As I was working on the poem, I came across an NPR program about entanglement, a phenomenon in quantum physics where two atoms can become connected in such a way that if one remained on Earth and the other were sent to the Moon, changes imposed on one of the atoms produced the same changes in the other, however distant. I thought about the entanglement between writer and composer, between our creative partnership and the performers, and between the performers and audience. These collaborations would likely represent a brief period of our lives, but I wondered if the connection would remain to influence us later.

I also looked at the murmurings of the heart, listened to recordings of heartbeats. The whoosh, the lub-dub. I considered how physicians monitor heartsongs to understand what is happening inside of us, and I thought about how people who can appear very similar can have subtle or significant disparities in their underlying anatomy, producing a heart murmur, for example. I read about the rare people with situs inversus, a condition where the internal organs are reversed. I imagined a doctor believing that such a person’s heart was weak, absent even, simply because they didn’t know how or where to listen.

This poem is my attempt to explore the importance of the act of listening, of learning to recognise and accept difference, and of how the interaction between people affects the rhythm of the heart, just as music does. I was also influenced by John Cage, the anechoic chamber, 4’33”, and how sometimes silence is necessary to hear one’s own rhythms, one’s own voice.

My atheism can cause me to be contrary, wilful, and defensive. Sometimes, my queerness can do the same. I wanted to learn how to listen, to find that common ground. This collaboration was an opportunity to test the surety of my identity, to be receptive, yet strong.

I finished the first draft, sent it to Jared, and waited anxiously for a response. When it came, I was both grateful for the sophistication of his feedback and resistant to the proposed edits. The piece was too long. Some of the lines would be cumbersome when sung and set to music. The introduction of the antagonist was too jarring.

The overall response was, however, enthusiastic, appreciative, and sensitive:

“I know how frustrating it is to have someone manhandling your work [….] Hopefully these suggestions are helpful and not frustrating! I know that often times, for me, it takes someone contesting some decision I make in writing to make me realize why I put it there in the first place […] I look forward to seeing what comes next!!”

This was what I had been excited about, the opportunity to be challenged, to have someone read my work and question it.

I edited, taking into consideration Jared’s suggestions about how the music could do some of the heavy-lifting for the piece’s motifs, allowing me to cut a lot of the repeated lines and phrases.

I sent the next draft, and waited.

The response this time was more of a challenge. Jared wanted to cut more and, as I saw it, to cut out the very heart of the piece, its nuance, its oddity, the entire reason for its being. The deliberate ambiguity of the poem’s final line was problematic; Jared suggested I make it less ambiguous.

What was left sounded like an ode to lost love, not a poem about the peculiarity of existence, of selfhood, of maintaining identity when a special kind of heartbreak is dismissed and silenced. Ambiguity was the very essence of the piece. To lose ambiguity would be to erase myself from the writing, as well as to strip it of the openness intended to foster uncertainty and invite interpretation from the audience who will hear the piece on June 5th.

I went back to an earlier draft and made cuts where cuts could be made. I believe that the final poem, which Jared has now so brilliantly set to music, remains delightfully ambiguous. He was right that the music could carry the themes of the piece, and although we have had some back and forth on the need for silence and softness, for repetition and circularity, I am proud of our art song, Arrhythmia.

Over the next few weeks the score will be in the hands of ASL’s performers, and I am incredibly excited to hear what they make of it. Writing can be such an isolating endeavour, and I’m so very grateful to be part of this year’s Art Song Lab intake and to have met Jared. Our unlikely collaboration has resulted in something beautiful and timely, giving a poem the space and respect to retain its queerness, and I mine.

Arrhythmia, the art song resulting from this collaboration, will be performed at Art Song Lab’s 2015 Concert, Playing with Fire, on June 5th. For more details see artsonglab.com.

{ 0 comments… add one now }

{ 1 trackback }